Illustrator Jose Pimienta

Author Allan Wolf

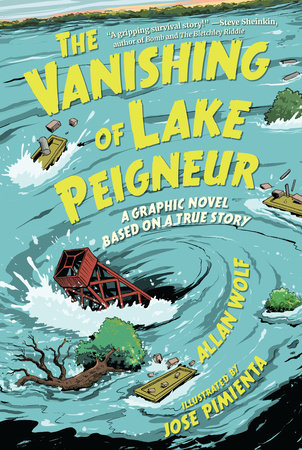

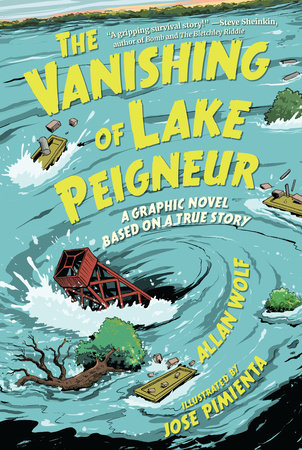

In today’s Author/Illustrator Spotlight, Landra Jennings chats with author Allan Wolf and Illustrator Jose Pimienta about their new middle-grade novel, The Vanishing of Lake Peigneur: A Graphic Novel Based on a True Story (Candlewick Press, October 7). They share the inspiration behind the novel, their creative processes and a little advice for those just starting out!

A Junior Library Guild Selection

Publisher’s Weekly Top 10 Middle Grade Graphic Novels, Fall ’25

“A riveting page-turner that will have readers eager to learn more about the topic.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

Book Summary:

The strange, true tale of a Louisiana lake that vanished—taking with it every fish below and every boat and barge above—told in a gripping and accessible graphic format.

The strange, true tale of a Louisiana lake that vanished—taking with it every fish below and every boat and barge above—told in a gripping and accessible graphic format.

Home to catfish and crawdads, shrimp and spoonbills, even a gator or two, Lake Peigneur—pronounced “your pain,” only backward—bustles also with human life. Each day, the bean-shaped freshwater lake and its shores hum with folks going about their work: a devoted gardener’s apprentice and his dogs, fishermen, oilmen drilling at Well P-20, and the fifty-one miners employed by the Diamond Crystal Salt Mines. For most, November 20, 1980, began as “just another day on the lake.” But as the lake itself reflects, humans had, over time, left behind a honeycomb of salt highways deep beneath its surface, and water and salt mix all too well. Bracing, suspenseful, and packed with dramatic illustrations and dense end matter, this story of a catastrophic accident—narrated with the homespun voice of a “tall” tale, but true nonetheless—will amaze science and history buffs alike.

Interview with Allan Wolf and Jose Pimienta

LJ: Welcome to the Mixed-Up Files, Allan and Jose! Thanks for joining us today. I’m so intrigued by this new book and I can’t wait to hear your thoughts on its development. Let’s start with you, Allan. Where did you get the initial inspiration for The Vanishing of Lake Peigneur?

AW: Back in 2007, while visiting schools and libraries in southern Louisiana, I noticed there was a chimney sticking up from the surface of Lake Peigneur, near New Iberia. So, I started asking questions.

I learned that Texaco, while exploring for oil in 1980, sent a 14-inch drill bit into the bed of a shallow1200-acre freshwater lake, piercing a salt-mine below, causing 3.5 billion gallons of water to drain like a bathtub. The resulting whirlpool and sinkhole, sucked in eleven barges, two oil derricks, a couple houses, a tugboat, a fishing skiff, and sixty-eight acres of a nearby ornamental garden. The disaster also created a 400-foot geyser and a 150-foot waterfall. The lake drained in four hours, then began to refill, via the Delcambre Canal, with saltwater drawn from the Gulf of Mexico, nine miles away! The A&E Channel featured the story in 2003 or so, but otherwise it seemed like very few people had even heard of this event. The details were so compelling, I had to tell it.

Junius Leak and the Spiraling Vortex of Doom

LJ: Allan, how does this title relate to your other recent release, Junius Leak and the Spiraling Vortex of Doom?

AW: The Vanishing of Lake Peigneur and Junius Leak and the Spiraling Vortex of Doom are siblings, raised together in the same house but choosing to grow in different directions. Junius Leak is a middle-grade historical fiction novel in prose, using the facts of the Lake Peigneur disaster as a backdrop for the book’s fictional characters. Junius Leak is a twelve-year-old kid sent to live with his mysterious uncle in a houseboat on Lake Peigneur near Delcambre, Louisiana.

AW: The Vanishing of Lake Peigneur and Junius Leak and the Spiraling Vortex of Doom are siblings, raised together in the same house but choosing to grow in different directions. Junius Leak is a middle-grade historical fiction novel in prose, using the facts of the Lake Peigneur disaster as a backdrop for the book’s fictional characters. Junius Leak is a twelve-year-old kid sent to live with his mysterious uncle in a houseboat on Lake Peigneur near Delcambre, Louisiana.

The factual disaster becomes a symbol of Junius Leak’s own coming of age. But to make the world of Junius Leak as authentic and historically accurate as possible, I had to do a lot of research. Then to synthesize my research, I wrote a 60-page prose story of what actually happened so that I could elegantly combine my fictional plot with the factual events. My historical fiction novels often have very extensive back matter. Long-story-short, the back matter of Junius Leak was so compelling, that it demanded we turn it into a book of its own. And that’s how The Vanishing of Lake Peigneur was born. It was my editor at Candlewick Press, Katie Cunningham, who suggested we tell the story in graphic form.

On a somber note, Katie Cunningham passed away this July 4th. Just three days after Junius Leak was published. And three months before the publication of The Vanishing of Lake Peigneur. She was 43. I miss her terribly.

Learning about the Lake

LJ: I love hearing about the relationship between the two books though I am so sorry to hear about Katie. What kinds of research did you do to be true to this story?

AW: I read every newspaper article I could find from the 1980s, along with many government documents reporting and analyzing what took place. The newspapers would sometimes contradict one another, so I looked to official documents from the Mining Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) to get my final numbers. I stalked my way through a labyrinth of Cajun names on FaceBook. I looked at several hundred photographs. I interviewed, in person, a handful of survivors and their relatives—including the 95-year-old captain of the tugboat, Charlie, who narrowly escaped being flung from a waterfall formed by the collapsing earth. Since I started my research in 2007, a few interesting podcasts have added to the story as well. But the in-person conversations I had with first-hand witnesses was my most valuable research tool.

To the Heart of The Vanishing of Lake Peigneur

LJ: What do you hope readers take away from this novel?

AW: Over all I’d like readers to see how it is possible to act courageously even when we are afraid. That is the very definition of courage: to take action in spite of fear and self-doubt. In their own individual ways, both The Vanishing of Lake Peigneur and Junius Leak and the Spiraling Vortex of Doom are stories of ordinary people acting heroically in the face of extraordinary circumstances. That’s when we find out who we really are.

Also, Junius Leak models for us how we don’t have to hide our true selves to make others more comfortable. Sometimes you get tired of trying to fit in. Sometimes you just want to be yourself. It is your choice to make.

On Writing

LJ: What’s your favorite thing about being a writer and story-teller?

AW: I have always identified with “being a writer,” but the early romance has always butted heads with the mundane needs of life. Being a professional writer for kids these days requires a lot of social media, marketing, conferences, bookstore events, school visits—all of it with only a tangential relationship to the actual act of writing books. But that writing itch always lurks. We all need to be the makers of something. If that need isn’t met, we whither. I guess the thing I really love about being a writer is the writing. I can write my way to discover that place, that spot, that just-right, water-tight safe space inside my head where I can go to find myself in my imagination.

What’s Next for Allan?

LJ: Is there anything else you’d like us to know?

LJ: Is there anything else you’d like us to know?

AW: Yes. The year 2025 has been a big one for me. In addition to the two books discussed here, I have a new poetry collection out, The Gift of the Broken Teacup: Poems of Mindfulness, Meditation, and Me. It is brilliantly and beautifully illustrated by Jade Orlando. These are fun yet thoughtful poems about self-regulation, self-care, and self-esteem. Of all my poetry collections to date, this one is the most personal. This book was my chance to explore what it means to have character and an intrinsic sense of self-worth. And it gave me a chance to share the ways I have learned to deal with anxiety and to practice self-care. The Gift of the Broken Teacup is sort of an owner’s manual for the soul.

The Illustrations

LJ: Now to you, Jose. The illustrations are phenomenal, starting with the cover. There’s so much energy that jumps right off the page. What excited you most about this project?

JP: The defining factor that excited me the most was that the story’s narrator would be the lake itself. I love stories about places, so, as much as there are many amazing people in this story, the point of view being the land drew me in, immediately.

LJ: How did this project differ from some of your other titles?

JP: This story is non-fiction, which is a first for me. Also, it involves so many people, so, keeping track of a large cast of characters was something I had never done. And! this is the first book I’ve drawn where all the characters are adults. Most of my books feature either teenagers or kids with some adults in there. This one was all grown-ups. But there’s puppies, so…

Jose’s Creative Process for Illustration

LJ: We all love puppies! What is your creative process like? What time of day do you do your best work and what medium do you use?

JP: For the most part, I like to listen to music related to the topic of the story I’m working on. I helps me to stay in the tone of the story. Unless I have errands to run or other engagements, I like to start drawing as soon as possible in the day, right after I finish cleaning up after breakfast. And I like it when drawing is the last thing I do before going to sleep. Everything in between can be different depending on the day. So, I draw a while, goof for a bit, run errands, meet with friends, draw some more, go for a bike ride, eat something, draw more, and so on.

JP: For the most part, I like to listen to music related to the topic of the story I’m working on. I helps me to stay in the tone of the story. Unless I have errands to run or other engagements, I like to start drawing as soon as possible in the day, right after I finish cleaning up after breakfast. And I like it when drawing is the last thing I do before going to sleep. Everything in between can be different depending on the day. So, I draw a while, goof for a bit, run errands, meet with friends, draw some more, go for a bike ride, eat something, draw more, and so on.

Generally, I draw with a mechanical pencil on 9×12 Bristol board or drawing paper. Then I ink my drawings with microns and brush pens. After that, I scan the pages and letter my comics digitally, because I do a lot of re-writes, so… this helps keeping the dialogues flexible. Lastly, I color digitally because it’s faster. I also prefer to do each book in passes. I like to do the entire book in pencil and then ink the whole book, and so on. Some people prefer to work in batches or one finished page at a time, and that’s great- but I can’t. I want to minimize the amount of gear shifting I do.

For writing, my process is an entirely different story. But more on that some other time.

The Path to Becoming an Illustrator

LJ: How did you get started along the path to becoming an illustrator?

JP: I’m not sure when it started. A cliché answer is “I never stopped drawing. I’ve just been doing this my whole life.” And that’s mostly correct. But as a professional, I can’t think of a definitive starting point. I went to art school, where I met a lot of amazing people I wanted to collaborate with, and that got me some work, but I also wanted to write and draw my own stories, so I did that as well. After art school, I came to Los Angeles in the hopes to work in the film industry, and I kept getting work here and there while I was making my own comics. At some point, I realized I was making a living drawing, so “Yay!”

I guess how I got started is I just kept telling people I wanted to draw and I showed them what I was working on. Some of that lead to work and some of it didn’t. Along the way, I made cool friends and got to collaborate with wonderful artists.

Advice for Those Just Starting Out in Illustration

LJ: What advice would you have for a beginning illustrator?

JP: Hmm… first I’d ask the illustrator what their goals are. Then, I’d hope I have useful advice for their specific path, or at least point them in the direction of other illustrators who do something similar so they can get better guidance. But as a general advice, I go with this:

Explore. Try things out. Find what works for you and approach everything with genuine curiosity. Experiment with mediums and see what catches your interest. Learn as much as you can from experts, but dare to go further than they have. Also- get comfortable with failure. Learning requires it. But pay attention and ask if it’s worth trying again. Lastly, Make friends. Be friendly. Be kind. Be sincere. Most people want to collaborate with someone they know or someone they like. So, show your work. No one’s going to hire you if they haven’t seen what you do. Oh! And of course: keep practicing the fundamentals.

I hope that’s useful, but if not, ask other illustrators. (And that’s my point: Ask and talk to as many as you can. We all want to see more art. So we’d love to see yours.)

Visiting the Lake

LJ: Is there anything else you’d like us to know?

JP: Only what you’d like to ask me, hehe. I’m not sure how to answer this, other than working with Allan was fantastic and this book was a phenomenal project. I’m so happy I got to draw this. Oh! Big story I like to share. When I first started drawing this, I wasn’t sure how to research this, since it’s non-fiction. I wanted to get as many details as possible correct, so, on a whim, I went to see the actual lake and I can’t tell you how much help that was. Visiting the lake was a terrific experience. Big thank you to everyone who answered my questions and their meals are top notch. If you get a chance to visit the area, by all means, it’s a delight.

Lightning Round Questions:

No MUF interview would be complete without our lightning round, so here we go…

For Allan Wolf:

Coffee or tea? Both.

Coffee or tea? Both.

Sunrise or Sunset? Sunrise.

Favorite city (besides the one you live in): Asheville, NC

Favorite books from childhood: Are You My Mother? By P.D. Eastman and Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel by Virginia Lee Burton.

Favorite ice cream flavor: Banana

If you could choose a superpower, what would it be? The ability to flood others with any emotion so that emotion then becomes their own.

For Jose Pimienta:

Coffee or tea? Tea.

Coffee or tea? Tea.

Sunrise or Sunset? Sunset.

Favorite city (besides the one you live in): (In the world?) Hamelin, in Germany. But if we’re doing US only: Los Angeles (I live in Burbank).

Favorite book from childhood: “Matias y el Pastel de Fresas” by Jose Palomo.

Favorite ice cream flavor: Ube. Or anything chocolate.

If you could choose a superpower, what would it be? I’m very serious about this: Scent manipulation. Being able to control smells would amazing. Had a bad day? Not when it smells like a bakery in here. Supervillain attacking you? Make it smell so bad they’re incapable of focusing. Did you pass gas in public? No one ever has to know. OR teleporting, whichever is easier to acquire.

Thank you so much Allan and Jose for sharing with us!

About the Author and Illustrator

Allan Wolf

Two time winner of the North Carolina Young Adult Book Award, as well as Bankstreet College’s prestigious Claudia Lewis Award for Poetry, Allan Wolf is the author of picture books, poetry, and young adult novels. Booklist has named his historical verse novel, The Watch That Ends the Night, one of “The 50 Best Young Adult Books of All Time.”

Also a skilled and seasoned performer of 30 years, Allan Wolf’s dynamic author talks and poetry presentations for all ages are meaningful, educational and unforgettable. Florida Reading Quarterly calls Wolf “the gold standard of performing poetry.” Wolf believes in the healing powers of poetry recitation and has committed to memory nearly a thousand poems.

Wolf has an MA in English from Virginia Tech where he also taught. He moved to North Carolina to become artistic and educational director of the touring group Poetry Alive!. Wolf is considered the Godfather of the Poetry Slam in the Southeast, hosting the National Poetry Slam in 1994, forming the National Championship Team in 1995, and founding the Southern Fried Poetry Slam (now in it’s 27th year).

Jose Pimienta

Jo Pi’s almost full name is Jose Pimienta. They reside in Burbank, California where they draw comics, storyboards and sketches for visual development. They have worked with Random House Graphic, Iron Circus Comics, Dark Horse Comics, Disney Digital Network, and more.

During their upbringing in the city of Mexicali, Mexico Jo was heavily influenced by animation, music and short stories. After high school, they ventured towards the state of Georgia where they studied at Savannah College of Art and Design.

For Comics work, they are represented by Elizabeth Bennet of Transatlantic Agency.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Zombie Makers: True Stories of Nature’s Undead

Zombie Makers: True Stories of Nature’s Undead Catching Cryptids: The Scientific Search for Mysterious Creatures

Catching Cryptids: The Scientific Search for Mysterious Creatures Secrets of the Dead: Mummies and Other Human Remains From Around the World

Secrets of the Dead: Mummies and Other Human Remains From Around the World Carla Mooney loves to explore the world around us and discover the details about how it works. An award-winning author of numerous nonfiction science books for kids and teens, she hopes to spark a healthy curiosity and love of science in today’s young people. She lives in Pennsylvania with her husband, three kids, and dog. Find her at http://www.carlamooney.com, on Facebook @carlamooneyauthor, or on X @carlawrites.

Carla Mooney loves to explore the world around us and discover the details about how it works. An award-winning author of numerous nonfiction science books for kids and teens, she hopes to spark a healthy curiosity and love of science in today’s young people. She lives in Pennsylvania with her husband, three kids, and dog. Find her at http://www.carlamooney.com, on Facebook @carlamooneyauthor, or on X @carlawrites.

The strange, true tale of a Louisiana lake that vanished—taking with it every fish below and every boat and barge above—told in a gripping and accessible graphic format.

The strange, true tale of a Louisiana lake that vanished—taking with it every fish below and every boat and barge above—told in a gripping and accessible graphic format. AW: The Vanishing of Lake Peigneur and

AW: The Vanishing of Lake Peigneur and  LJ: Is there anything else you’d like us to know?

LJ: Is there anything else you’d like us to know? JP: For the most part, I like to listen to music related to the topic of the story I’m working on. I helps me to stay in the tone of the story. Unless I have errands to run or other engagements, I like to start drawing as soon as possible in the day, right after I finish cleaning up after breakfast. And I like it when drawing is the last thing I do before going to sleep. Everything in between can be different depending on the day. So, I draw a while, goof for a bit, run errands, meet with friends, draw some more, go for a bike ride, eat something, draw more, and so on.

JP: For the most part, I like to listen to music related to the topic of the story I’m working on. I helps me to stay in the tone of the story. Unless I have errands to run or other engagements, I like to start drawing as soon as possible in the day, right after I finish cleaning up after breakfast. And I like it when drawing is the last thing I do before going to sleep. Everything in between can be different depending on the day. So, I draw a while, goof for a bit, run errands, meet with friends, draw some more, go for a bike ride, eat something, draw more, and so on.

Coffee or tea? Both.

Coffee or tea? Both. Coffee or tea? Tea.

Coffee or tea? Tea.