credit: Elena Seibert (2012)

If you’ve ever had trouble coming up with book ideas, you may be encouraged to know Magic Tree House author, Mary Pope Osborne, struggled to find a method for Annie and Jack to travel back in time. She tried seven different ways, including a cellar, an artist’s studio, and a museum, before she and her husband spotted a tree house during a Pennsylvania vacation.

And the rest was history…

The first Magic Tree House book came out in 1992. Since then, she has written 67 books in the series, and more than 191 million copies have been translated into 39 languages and shipped to over 100 countries. And now, the Magic Tree House books are coming out as graphic novels.

If you’re wondering how Mary Pope Osborne can write so many books, she once said she can work up to 12 hours a day and 7 days a week. But she also had to set aside time for other activities, such as traveling to schools, creating programs for teachers, and supporting writing organizations.

We’re delighted to have this beloved author here with us on our blog today. Welcome, Mary! Thank you for joining us and answering some questions for our readers (and yours). We’re really excited to see your books come out as graphic novels.

Did you have any childhood dreams for when you became an adult? If so, did they come true?

I had big dreams as a child. I wanted to be a movie star, a singer, a dancer, a TV announcer, a star athlete, a famous politician. As a child, I never actually dreamed of becoming a children’s book author. But now after forty years of writing books, I can say I’ve had the best career I ever could have imagined.

You moved many times when you were young. How did you adjust to new situations?

I have two brothers and a sister, and we were all best friends. (We still are). So moving was easy when we all discovered our new surroundings together. We treated each move as a new adventure.

How did the unusual places you lived—across from an ancient castle in Austria or in a fort with a moat in Virginia—influence your imagination and spur your storytelling abilities?

I think these historic environments gave a sense of timelessness to childhood. It felt natural for me to later write stories about a brother and sister who travel to long ago times and faraway places.

In your books, Annie is the fearless one, and Jack is the worrier. Which character is most like you? And why?

In many ways, I was more like Annie when I was young. I threw myself into everything, often taking a leap before I really understood a situation. Today I am more like Jack. I worry about many things, but I’ve learned how to seek advice or gather information to handle my feelings.

What were some of your fears when you were young?

Fire ants, wild dogs, tsunamis, jellyfish, spiders, ghosts, centipedes…That’s just a few items on a very long list. But happily, all those fears seem baseless now, as I was never harmed by any of these things.

What advice would you give to your younger self?

Don’t be afraid. Don’t worry. Just personally try to do the next right thing, and everything will work out.

You’ve written so many books. Do you have any tips for coming up with fresh and unique ideas?

ideas?

Don’t allow yourself to think you’ve run out of ideas. There are an infinite number of possibilities for a story. Study your personal world – your family, friends, pets, and natural surroundings. Read lots of books and gather inspiration from the past. Study history, animals, insects, other cultures, mythology, fairy tales, and the Bible. A zillion ideas are out there, waiting for writers to discover them.

Can you tell us about your family’s involvement with the books?

Soon after I started writing the fictional Magic Tree House books, my husband Will started the nonfiction line called the Magic Tree House Fact Trackers. His books are factual companions to my adventure stories. Then, Will turned his attention to creating a Magic Tree House planetarium show, and my sister Natalie took over the nonfiction Fact Trackers and has written more than 40 of them, along with many MTH activity books. About fifteen years ago, Will began work on a series of Magic Tree House musicals with our best friends, composer Randy Courts and playwright Jenny Laird; and their team now has nine shows that are performed around the country. Currently, Jenny Laird is adapting the Magic Tree House books into graphic novels. And Will, Randy, and Jenny are working on a Magic Tree House animation.

That’s so exciting that the books have appeared in so many different forms, including shows and graphic novels. And the nonfiction companion books are so helpful in providing additional information about the topics.

That’s so exciting that the books have appeared in so many different forms, including shows and graphic novels. And the nonfiction companion books are so helpful in providing additional information about the topics.

Do you have any message or advice for the teachers and parents who will be sharing your book with their students and families?

I urge teachers and parents to have a good time while reading Magic Tree House stories with children. Share your readers’ excitement as they imagine themselves overcoming the adversities that Jack and Annie face, and review with them new knowledge they’ve gained about the world.

Teachers can go to the wonderful Classroom Adventures site for resources, teaching tools, and free Title 1 books.

What do you hope readers will take away from your books?

I hope they take away a love for reading, and a love for learning more about world history, heroes, animals and nature – and themselves. Jack and Annie overcome many challenges by simply being good people.

Can you share what you are working on now?

I’m working on the first of a new quartet of books called Magic Tree House History Heroes. The first hero Jack and Annie visit is twelve-year-old Mary Anning who lived on a rocky shore of England in the early 1800’s. Though Mary had no money and no schooling, and suffered from a tragic home life, she made a discovery that helped change the way we think about the history of the world. The story of Mary Anning is unbelievable, but true.

We appreciate you taking the time to answer these questions, and we look forward to the launch of your graphic novels as well as the Magic Tree House History Heroes.

A SNEAK PEEK INSIDE A MAGIC TREEHOUSE GRAPHIC NOVEL

If you’ve ever wondered how graphic novels are made, you’ll enjoy this special bonus to Mary Pope Osborne’s interview. Jomike Tejido, one of the illustrators for the Magic Tree House graphic novels, has agreed to share some of his secrets and show us a few of his early drawings. I asked Jomike because he illustrated my middle-grade novels in the Second Chance Ranch series.

Hi, Jomike, so nice to have you here today. I’m really excited to see inside your graphic novels. And we have some questions for you as well. Thanks for agreeing to an interview.

Hi, Jomike, so nice to have you here today. I’m really excited to see inside your graphic novels. And we have some questions for you as well. Thanks for agreeing to an interview.

Please share a little about where you grew up and any books you liked.

I grew up in Manila, Philippines—where I still live now with my family. Growing up, I liked reading Spot, Babar, Berenstein Bears and Georgie the Ghost. My favorite was Where’s Waldo, though since I liked the visual storytelling it had in its tiny drawings. In later grades, I liked the detective series Hardy Boys.

Can you share a childhood story about how you first became interested in art?

I first got into art with my dad, as he was an architect and practiced in a small family-run home-office. He would teach me in the sidelines of his actual work as there were a lot of scratch papers around. The setup was just my parents and a few draftsmen/women who came in and out of an extra room in our house. It was the time when no computers were used for drafting. The only use of the computer at the time was making charts and lists. I had a lot of physical art materials from the office at my disposal. My favorites were large papers and watercolors, and they were always within reach. I only got into trouble if I did not return them in their proper places. To remedy this, I setup a little table within their office so I could have my own space and little chair. I told people not to bother me, as I was also “busy.”

When did you know you wanted to be an illustrator?

In high school, a local newspaper opened a kiddie magazine called Junior Inquirer where kids could contribute art, write and illustrate—and actually get paid for it. I repeatedly sent submissions to them just so I could buy my own video games. The editors saw my enthusiasm and told me there was an organization dedicated to the craft I was beginning to like, called Ang Ilustrador ng Kabataan (Ang InK), which means Illustrators for Children. I joined the org as the youngest member at 18, and learned the ropes around publishing and met the people of the local industry. My love for the craft led me to have my first publication at that age, and then become an author-illustrator at age 20. I learned from the illustrator’s group how the industry works in a global scale, particularly how artists from the US work with agents. I kept the idea at the back of my mind as a long-term plan as I went on publishing around 70 titles throughout my college years (where I took up Architecture). The opportunity came in 2007 where I was able to sign with MB Artists, NYC, and I have been working with them ever since for my books outside of the Philippines.

Did you ever read the Magic Tree House books when you were young?

I never saw a Magic Treehouse book when I was little. But when my first daughter was at a starter age for reading in 2015-2016, we found them in a local used bookstore where I often bought books in bulk for research and self-study. We turned Magic Treehouse into bedtime stories for several years until she started reading on her own and moved up to novels. I recall looking at the illustrations and wished I could have a long serialized project like that someday. I even felt sad that Magic Treehouse was already done and something that fun would not be repeated again.

What do you like most about being an illustrator?

I like being able to draw a lot, every day. As an artist, I juggle two paths- as an abstract painter and as a digital illustrator. Both work in different ways as they serve two interests I have. As an illustrator, I like making pictures that are light, funny, adventurous and whimsical. I don’t feel like I am working when I do it. It is just like drawing on that little desk I setup for myself back when I was little (and yes-, when the process starts, I still dislike being bothered). 😀

What is the most challenging part of illustrating a graphic novel?

The most challenging part is the layout. Unlike illustrating picture books where the text occupies (usually) a single block in a page, graphic novels have panels. The panels are like little pages where the order of the speech balloons have to go a certain flow, and those have to come in first to make sure the dialogues fit. Second—as it is a nonfiction graphic novel, I also find it challenging to find the references that would fit the tiny panels and convey the right amount of detail needed. Lastly, as an inker/line artist for the series, I find myself often feeling sleepy when I do not see colors for a long time! In contrast to my other job as a painter, linework is easy with the iPad as my main tool, but maybe I just have to remind myself to get up and stretch or take a walk after a few pages!

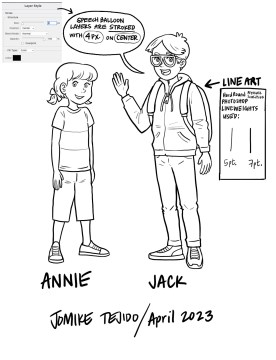

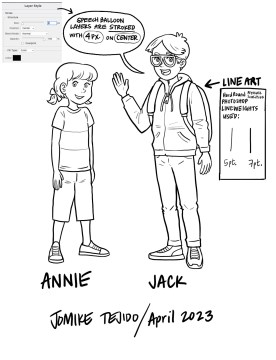

Can you tell us how the characters were developed for the illustrations?

The characters were based off several reference specifications, from written descriptions, the new Jack and Annie in the main graphic novels and also the original grayscale versions. I had to find a middle ground that would make my Jack and Annie still resemble those but also look like my own work. It took several backs and fourths. It was soooooo stressful because I really wanted to get it and surprise my daughter that I would be working on the series we used to read for bedtime! I was so happy I got picked.

Do your characters differ from those in the books? If so, how?

I would say my characters look similar to those in the main graphic novel but are probably simpler due to the fact that they don’t necessarily have to be in adventurous/action scenes for the Fact Trackers. This balances off my time to focus on the detailing of the factual/technical illustrations.

Can you tell us about your art technique?

My art technique is purely digital and done on an iPad. It involves one of the clean ink brushes that produces thin lines and tapers when I do fast gestural strokes with my stylus. It relies heavily on photos of the objects, people, animals and places that are needed for illustrating the facts, so those usually are on a separate screen where I copy them and reduce details to make it look like they are part of the comic world that my Jack and Annie live in.

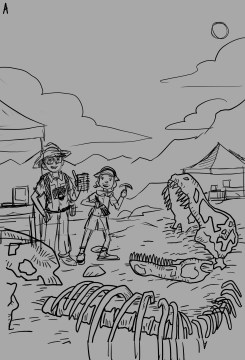

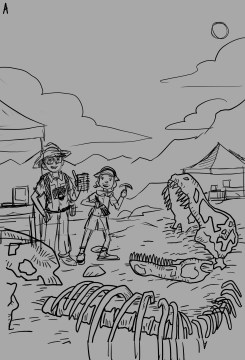

The process starts with rough sketches which look messy. I use a gray backgound so the contrast of my lines won’t be too stark. The main purpose of this stage is to allot speech balloons that can fit the amount of dialogue allotted in each panel. We can call it the problem-solving stage. My thoughts in this stage are usually like “How do I cram all these data in such a small space?!” or “Do I have to draw the stuff that’s BEHIND the speech bubble?” (Of couse I still do!)

Since this involves a lot of eyeballing and guesswork, it takes a lot of trial and error until I get the right size and shape of ellipses to encase the words. I make sure I have ghosted out rulers around my pages as a template, so I do not go over the side edges or the central gutter.

The rough sketches are sent to my editors and then returned to me with comments for improvement. Luckily, I get to ink them already after this stage. I only have to re-sketch things when big movements are needed. I don’t make a tight sketch round anymore as the time it takes to do this is almost the same time as I would take to already go into the final inking. That would be the fun stage. There is something about the final ink rendering stage that triggers something in my mind that tells me, “Now let’s make these pages look nice.”

Inked cover of Fact Tracker: Dinosaurs

It’s been a lot of fun to see how you work on pages in the graphic novels and to see them go from rough sketches to finished pages.

In addition to working on the Magic Tree House graphic novels, please tell us about some of your favorite books that are already out.

My favorite is There Was an Old Woman Who Lived in A Book (Jimmy Patterson/ 2019) as it was my debut as an author-illustrator in a US publication. I got a chance to have an author visit for this title in some schools around Manhattan and Brooklyn.

My favorite is There Was an Old Woman Who Lived in A Book (Jimmy Patterson/ 2019) as it was my debut as an author-illustrator in a US publication. I got a chance to have an author visit for this title in some schools around Manhattan and Brooklyn.

A recent book I worked on that was fun and imaginative was Addy’s Chair to Everywhere by Debi Novotny, and I loved how the book kept jumping from real world to imagined world throughout the story.

I also loved Second Chance Ranch (Jolly Fish Press). Aside from the fact that it spanned a good number of titles (series work is always AWESOME for me), I got to do an aerial view map of the setting, which I always wanted to do for MG titles.

Another title coming this August is Live Big with Catch-M, written by Kat Kronenberg. It has a lot of animals and galaxy scenes which I’ve always loved  to paint digitally.

to paint digitally.

What are you working on now?

I am now working on the fourth installment of the Magic Treehouse Graphic Novel Fact Trackers and the theme is Mummies and Pyramids. It is especially fun to do as it taps into my architectural roots and the scenes I am currently drawing involve a lot of rooms and isometric views of rooms, which is also reminiscent of video games I used to play.

Locally, I am working on a series of papercraft books called Foldabots. They are D-I-Y cut-out robots kids can build, and they actually transform into cars, animals and other cool stuff. Foldabots Toy Book 1 (Anvil Publishing house) has QR codes linked to my YouTube channel where I guide my builders though the assembly process of each character.

Thanks so much for sharing your process with us, Jomike. We look forward to seeing your latest books. And we’re eagerly awaiting the Magic Tree House graphic novels, which come out this week.

Like this:

Like Loading...

In today’s Author Spotlight,

In today’s Author Spotlight,  A girl with psychic abilities and a boy with mysterious powers must unravel secrets and battle dark forces in order to save their world in the final Ravenfall adventure.

A girl with psychic abilities and a boy with mysterious powers must unravel secrets and battle dark forces in order to save their world in the final Ravenfall adventure. KJ: In addition to returning to everyone’s favorite inn, this book brings Colin’s and Anna’s journeys full-circle with the return of some threads everyone thought were tied up. RAVENGUARD delves back into Irish mythology, but like all the books in the series, the biggest challenges Anna and Colin face are their own doubts.

KJ: In addition to returning to everyone’s favorite inn, this book brings Colin’s and Anna’s journeys full-circle with the return of some threads everyone thought were tied up. RAVENGUARD delves back into Irish mythology, but like all the books in the series, the biggest challenges Anna and Colin face are their own doubts.

Tea!!!

Tea!!! Dealing with Dragons by Patricia C. Wrede.

Dealing with Dragons by Patricia C. Wrede.

ideas?

ideas? That’s so exciting that the books have appeared in so many different forms, including shows and graphic novels. And the nonfiction companion books are so helpful in providing additional information about the topics.

That’s so exciting that the books have appeared in so many different forms, including shows and graphic novels. And the nonfiction companion books are so helpful in providing additional information about the topics. Hi, Jomike, so nice to have you here today. I’m really excited to see inside your graphic novels. And we have some questions for you as well. Thanks for agreeing to an interview.

Hi, Jomike, so nice to have you here today. I’m really excited to see inside your graphic novels. And we have some questions for you as well. Thanks for agreeing to an interview.

My favorite is

My favorite is

to paint digitally.

to paint digitally.