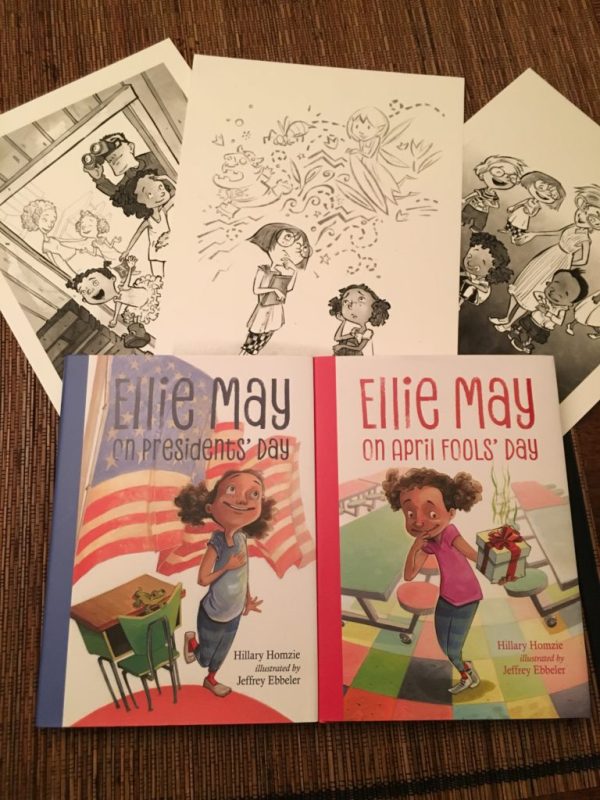

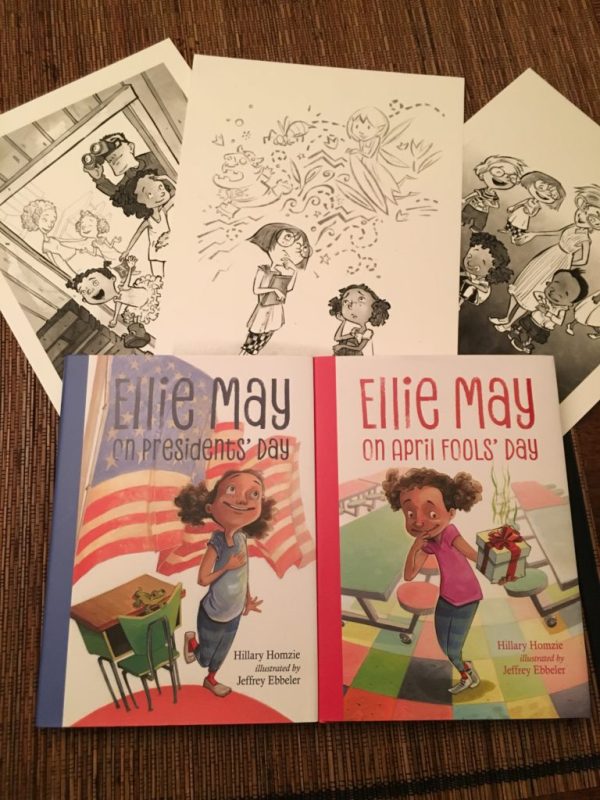

When my editor sent me cover sketches of Ellie May on Presidents’ Day (Charlesbridge, December 2018) and Ellie May on April Fools’ Day (Charlesbridge, December 2018), I was bursting with happiness. Illustrator Jeffrey Ebbeler truly understands the essence of this enthusiastic kid who has been in my head for such a long time.

When my editor sent me cover sketches of Ellie May on Presidents’ Day (Charlesbridge, December 2018) and Ellie May on April Fools’ Day (Charlesbridge, December 2018), I was bursting with happiness. Illustrator Jeffrey Ebbeler truly understands the essence of this enthusiastic kid who has been in my head for such a long time.

And yet for months, I couldn’t really share the covers of my chapter books with anyone, but then the covers were shown at ALA, as well as a School Library Journal webcast Behind the Scenes: SLJ in Conversation with Children’s Books Editors. Additionally, the covers were sent to Indiebound.org, Barnes & Noble, Amazon and other bookselling sites. So yes, by then the cat was out of the bag. And so today is a big deal because it’s the first time I’m officially showing them off and talking about them.

Even though Ellie May on Presidents’ Day and Ellie May on April Fools’ Day are my tenth and eleventh books, this whole publishing process still amazes and, at times, overwhelms me because there are so many things that need to happen, much of which I have little to do with. And with chapter books–that would be all of those interior illustrations–and plus, the covers.

So now I get to interview illustrator Jeffrey Ebbeler about how all of this came together. And you all get to enter for some awesome prizes. More on that later.

Oh, but first you probably will want to know a little bit about the series. It stars the irrepressible Ellie May. When it’s time to celebrate holidays in the classroom, second-grader Ellie May can get a little overzealous, often learning about honesty and patience through trial and error. In Ellie May on Presidents’ Day, the second grader struggles with how to be honest and be a leader (wow, I no idea how timely this topic would be when I first wrote this one). Ellie May on April Fools’ Day ultimately debates how to be funny and not hurt people’s feelings.

Now, without further ado, here’s Jeffrey to tell us about the process of creating the covers, which I think are adorable (but I’m very biased!).

Where did the inspiration for the covers come from?

I have the same experience that I think most readers have. When I read a new story, a little movie plays in my head. When I read the descriptions and dialogue, I imagine how all of the characters might look. I try to imagine every small detail, from the kind of house they live in, to the clothes that they wear.

Ellie is such an exuberant character. She bursts with excitement and enthusiasm. I felt really fortunate that I was asked to illustrate Hillary’s two books, and it came at it came at a serendipitous time for me. I have twin daughters that were in third grade last year (the same age as Ellie May) when I was working on this book. Ellie May’s personality reminds me so much of my daughter Olivia, and her friend Lizzy is like my daughter Isabel.

I used a lot of family photos as inspiration for the poses and facial expressions of those two characters.

I wanted both covers to focus on Ellie May and convey her wide-eyed excitement.

Take us through the process of how you created the covers?

When I am illustrating a book, I try to do the cover last. I always start by reading the story several times. I write lots of notes and do a bunch of doodles. Then I do a character sheet, where I draw every character. It’s really important that the characters look the same through out the whole book. Sketching a book takes a couple of weeks, and I always find that I am refining and adding new details to the characters as I go. That’s why I like to save the cover for last, because by then I have really worked out all of the characters individual mannerisms.

Did you start with pencil sketches or work on the computer?

I do most of my work the old fashion way, with pencils and paint. I sketch everything on paper, and the final art for the covers are painted. I do some additional work to the art in the computer, though. After I scan in the finished paintings, I do some retouching in Photoshop. I lightened up the background behind Ellie May on both covers in the computer, so she would be the focus of the cover.

Did you have hurdles or challenges?

I knew right away that the cover President’s Day should be Ellie May saying the Pledge of Allegiance. The biggest challenge was her pose. I did four or five different poses that ranged from her standing very seriously at attention, to some goofy poses. I think the end result is a good mix of respect for the flag and the excitement in Ellie May.

I worried more about the April Fool’s Day cover because pranks can be a dicey subject. I think Hillary did a great job in the story of having Ellie May think through some jokes and why some might not be a good idea to actually do to someone. The cover hints at one of Ellie May’s joke ideas without revealing too much. She does give someone a stinky gift, but it has a surprising result.

Any aha moments?

I had tons of moments working on these two books. I love reading a funny passage in a book and trying to think of a way that I can add to that joke with a funny image. Some of my favorite illustrations in the books are when Ellie May is researching little known facts about presidents or birds. I got to draw Abraham Lincoln covered in cats, and a cardinal taking a bath in a tub full of ants.

What medium did you use?

The cover art is done in acrylic paint on paper. The black and white art inside the book is also painted with a brush. I love painting fine lines with a liner brush. I like the look if it better than using pens or markers. All of the art has had some touchups that I do in the computer.

What do you hope the covers communicates?

What do you hope the covers communicates?

I hope Ellie May’s pose and facial expression communicate that she is enthusiastic, fun, a little mischievous, but also well meaning.

How many drafts did you do before you settled on what you wanted?

For book covers, I always try to present a bunch of different options. I showed about five or six different ideas for each book. I doodled about 20 ideas that I didn’t show because they weren’t quite right.

For the Presidents’ Day book, I did a sketch that ended up being the title page for the book. It was Ellie May dressed in Revolutionary War era clothing, holding the flag. I also sketched a cover that was a grid of presidential portraits with Ellie’s portrait in the middle.

For April Fools’ Day I sketched out several different April Fool’s jokes from the book. I also thought that it might be a fun and goofy image to have Ellie hanging upside down from the monkey bars, because she does that in both books.

In what ways is the final version different from your original concept for the cover?

The final versions were much more focused directly on Ellie May. Her face is the most important thing, and I hope that it will convey somethings about her personality, and get people curious to see what she’s all about.

How important is a cover to a book’s success?

It can definitely be important. I know I’ve picked up lots of books because they had intriguing covers. In the end, there needs to be a great story inside, and there is. It would be wonderful if my cover could help draw young readers in, to check out Ellie May’s adventures.

Anything new you learned from working on the Ellie May series?

I did learn a bunch of interesting facts about the presidents as well as the history April Fool’s Day. Two of my favorite facts were that in France, “jokers tape a fish to unsuspecting peoples backs on April Fool’s Day” and that George Washington’s false teeth were made from “gold, lead, hippo, cow and donkey teeth.”

Anything else you would like to share?

I want to thank Hillary for writing these excellent stories, and also for interviewing me about illustrating her books. I hope you will have as much fun reading them as I did illustrating them.

Oh, and here’s the giveaway part! It’s–drumroll. One high-quality print of an Ellie May illustration signed by Jeffrey Ebbeler AND signed paperback copies of Ellie May on Presidents’ Day and Ellie May on April Fools’ Day (these will be mailed in December) AND PDFs of both books.

How to register to win? Lots of ways. 1) Make a comment here. 2) Follow me on Twitter @hillaryhomzie. 3) Tweet about this and tag me on Twitter @hillaryhomzie 4) retweet my Twitter post about this post. If you do all four things, you will increase your odds of winning but you only need to do one thing in order to get registered. Good luck everyone!

Jeffrey Ebbeler has been creating award-winning art for children for over 15 years. He has illustrated more than forty picture books, including Melvin the Mouth, Captain’s Log: Snowbound and he is both the author and illustrator of George the Hero Hound. Jeffrey has worked as an art director and has done paper engineering for pop-up books. He and his wife, Eileen, both attended the Art Academy of Cincinnati. They have twin daughters, Olivia and Isabel.

www.jeffillustration.com

Hillary Homzie is the author of the forthcoming Ellie May chapter book series (Charlesbridge, Dec 18, 2018), as well as the forthcoming Apple Pie Promises (Sky Pony/Swirl, October 2018), Pumpkin Spice Secrets (Sky Pony/Swirl, October 2017), Queen of Likes (Simon & Schuster MIX 2016), The Hot List (Simon & Schuster MIX 2011) and Things Are Gonna Be Ugly (Simon & Schuster, 2009) as well as the Alien Clones From Outer Space (Simon & Schuster Aladdin 2002) chapter book series. She can be found at hillaryhomzie.com and on her Facebook page as well as on Twitter.

Like this:

Like Loading...

(Me, the first time seeing my book on the shelf)

(Me, the first time seeing my book on the shelf)