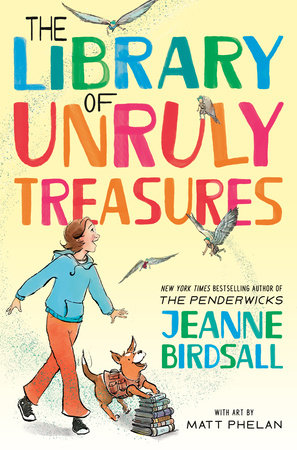

Jeanne Birdsall’s THE PENDERWICKS is as highly acclaimed and beloved as a middle-grade series can be, earning the National Book Award and becoming New York Times bestsellers. With her newest novel, THE LIBRARY OF UNRULY TREASURES, she creates a new world: one of tiny, winged creatures called Lahdukan and the adventures a girl named Gwen has with them in a library outside Boston. It’s a wild, fun, and heartwarming ride that is sure to delight Penderwicks fans and new readers alike.

Read below to discover the inspiration for this new book, thoughts on Lahdukan pronunciation and (incredible!) art, and the real Pumpkin the dog(s) in Jeanne’s life!

The opening of THE LIBRARY OF UNRULY TREASURES grabs readers with a series of diary entries that tease some of the magic to come. When did you decide to open the book like that, and what are you hoping readers will glean from it?

I knew I’d have to open the book in 1860s Edinburgh, if only to justify the research trip I took to Scotland. That’s only kind of a joke. Truly, once I’d wandered the neighborhood where my diarist lived, she became too real to be shoved aside as mere backstory.

I thought it would be fun for the readers to know more than Gwen does at the beginning of the story, to have them impatient for her to meet the Lahdukan. When she finally does, the reader already knows the Lahdukan are real and thus can enjoy watching Gwen become convinced. From that point on, the reader knows only what Gwen knows. They can be puzzled together, and I hope they are. I like a bit of a mystery.

Gwen is a character readers immediately pull for—what was the process like of creating her? Was she fully formed from the start, or was it a longer process, and how did Matt Phelan’s interpretation of her (and the other characters!) come to be?

I knew Gwen right away. It took me a while, though, to work out what made her who she was—both despite of and because of her rotten parents and lonely childhood. And even longer to figure out how to explain her past without a lot of exposition. I wanted the reader to understand how difficult it had been for Gwen, but without piling on too many gruesome details.

Matt illustrated a picture book of mine, Flora’s Very Windy Day, so I knew that our instincts and visual aesthetics were in sync. He got Gwen right away. (And gave her freckles. I pretend this was in honor of my freckles, but it may have been a coincidence.) We had to go back and forth for a while with Pumpkin, but that was my fault. My original text made her sound like a mythic monster, a tiny griffin with impossibly mismatched parts. Matt’s Lahdukan are masterpieces. Their combination of goofiness and dignity is right there in every painting. And the Lahdukan in flight! There’s one spread of them aloft inside the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum that makes me catch my breath every time I see it.

The detailed worldbuilding of the Lahdukan is such a joy to uncover in the book. You mention Mary Norton’s delightful The Borrowers as an inspiration for these tiny, wondrous creatures, but did you have any other influences on this world?

The Borrowers are an obvious reference point. Not only were the books written during my childhood—we were allreading them—but Beth and Jo Krush, the illustrators, lived in my neighborhood, a mile down the road. But the Lahdukan were woven from dozens of myths and stories, enriched by my fascination with Scotland, particularly the Highlands. Some of this came because of my Scottish blood, but lately I’ve been re-reading T. H. White’s The Once and Future King. He goes deeply into the Scottish Gaels (Gawaine and his peculiar brothers) and their resentment of the English. This must have lodged in my brain years ago, to come out now.

Plus, I’ve always wanted to be able to fly, haven’t you? The closest I could get was bestowing eagle wings on my Lahdukan.

Pumpkin the dog is a force throughout the book, and you mention in the introduction that you can’t write without a canine companion. Was Pumpkin always such an integral character, or did her role change through the drafting process?

Pumpkin was always going to be important to the story, but not being satisfied with mere importance, she upped her own role until she was vital. Just like my real dogs.

[Editor’s note: to see pictures of Jeanne’s own dogs, visit her website!]I appreciated the pronunciation guide at the end of the book and had so much fun with the Lahdukan names and background. Is that something you had thought through while writing and sounding out these splendid details?

No, but I should have! Because I don’t like reading my own writing out loud and I don’t listen to audiobooks, I didn’t think about it along the way, just merrily dreaming up names and words. It was only toward the end, when my own husband still couldn’t remember how to say Abarisruk or Zarakir, that I realized I’d need a pronunciation guide.

Although I don’t listen to audiobooks, I hope people will listen to this one. By an incredible stroke of luck—or maybe magic—we found the perfect narrator. Sorcha Groundsell grew up on the Isle of Lewis, one of the Outer Hebrides, west of Scotland and close to the Isle of Rùm, where the Lahdukan lived a thousand and more years ago. (See? Magic!) Her voice is gorgeous—light, quick, musical—exactly what the story calls for. Just wait until you hear her as the Lahdukan.

Do you have any other adventures in mind for Gwen, Pumpkin, and the Lahdukan, or are you returning to other book worlds (or elsewhere!) next?

I have dozens of other adventures in mind, going forward and backward in time. But speaking of time, alas, I don’t have enough of it. The Penderwicks took twenty years of my life, and almost certainly I don’t have twenty more to spend on another series. Where I’m headed next is still a bit fuzzy, but there will be pie and a dog, and I’ll have to learn some Italian.

Jeanne Birdsall is the National Book Award–winning author of the children’s book The Penderwicks and its sequel, The Penderwicks on Gardam Street, both of which were also New York Times bestsellers. She grew up in the suburbs west of Philadelphia, where she attended wonderful public schools. Although Birdsall first decided to become a writer when she was 10 years old, it took her until she was 41 to get started. In the years in between, Birdsall had many strange jobs to support herself while working hard as a photographer. Birdsall’s photographs are included in the permanent collections of museums, including the Smithsonian and the Philadelphia Art Museum. She lives with her husband in Northampton, Massachusetts. Their house is old and comfortable, full of unruly animals, and surrounded by gardens.

THE LIBRARY OF UNRULY TREASURES is available for pre-order until August 5th, 2025 and then wherever books are sold. Visit Penguin Random House for more information and to order!

Book Summary:

Book Summary:

For illustrations for Jazzy, I had my stylistic approach from that initial sketch. I was also inspired by

For illustrations for Jazzy, I had my stylistic approach from that initial sketch. I was also inspired by

Favorite book from childhood?

Favorite book from childhood?