STEM Tuesday’s Gone Graphic

Comics? We don’t need any of that nonsense in STEM.

What was that? No, I did not see the STEM Tuesday “Great Science Graphic Novel” book list for this month.

Bah-humbug! We didn’t have STEM books like that when I was a kid. Textbooks were perfectly fine for us.

No, my name is not STEMbeneezer Scrooge. Now, get off my lawn and leave me be. It’s time for my nap.

Who’s there? I thought I told you to skedaddle.

Aye! It’s a spirit.

Leave me be! I’m just an old STEM guy stuck in my ways. I’m going back to sleep before Wheel of Fortune comes on.

“STEMbeneezer, log on and follow me!”

What in the world? Another STEM spirit!

Smooth, Ghost of STEM Present. Real smooth. But I’m not going to get on the internet to scour bookstores.

Haven’t you heard of online identity theft and spyware?

Jeez, leave me be, I’m going back to sleep. And where do you come up with these “original” names, anyway?

What are you? You must be the Spirit of STEM Future.

Aack! Don’t beam me up, Scotty! I don’t want to go!

NOOOooo!!!

A hint? For what?

Help meeeeeeee!

Holy bad dreams. What happened? How long have I been asleep?

I know that answer!

Come, on! The answer’s easy.

Graphic storytelling is a great format for STEM books.

I’m a changed man. Textbooks have their place but the graphic novel format really does work well with STEM storytelling.

Graphic storytelling + STEM = Natural match

Using graphics to define a STEM concept has been a natural partnership for ages. I present the evidence.

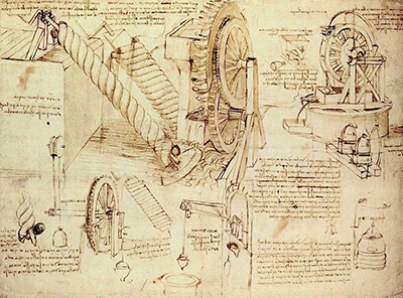

DaVinci designs are a graphical how-to manual

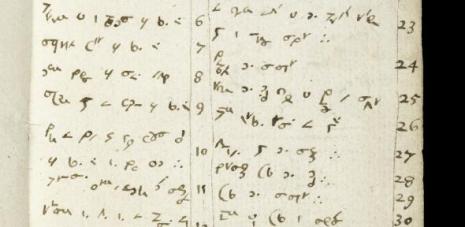

Galileo’s graphic notes on his observations of Jupiter’s moons

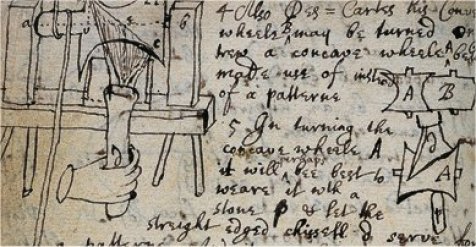

Sir Issac Newton’s Graphic Notes

Chemistry

If you have the reagents, you could probably make your own Vitamin A from this graphical reaction.

Maps of biological pathways

The Krebs Cycle, aka The “I wish I had a dollar for every time I memorized & forgot this pathway in my school days” Cycle.

TNF pathway from one of our lab’s publications. It tells the visual story of an E. Coli effector subverting the TNF inflammatory pathway.

Let the evidence show using graphics has worked in STEM since the STEM fields were born.

It’s only natural they work in the field of STEM storytelling, right?

Visual Storytelling

A picture is worth a thousand words.

UNDERSTANDiNG COMICS: THE INVISIBLE ART by Scott McCloud

This a book you must read whether you are interested in straight graphic storytelling or storytelling in general. It doesn’t matter if the storytelling is fiction or nonfiction, graphic storytelling can be a powerful option for a writer.

Sketchnotes

Sketchnoting is a great way to take notes for the visual-minded individuals. I follow Eva-Lotta Lamm and her work with sketchnotes. She offers a free, downloadable Mini Visual Starter Kit at her website to help you get started with sketchnotes.

Conclusion

Hopefully, you are now convinced that images and STEM go together. The graphic novel format for nonfiction and STEM books not only works, but it fits. Just as architects and engineers use a blueprint drawing to relay information to the contractor and specialists, STEM writers can use graphic storytelling to relay information to the reader.

Still not a believer? Go to the STEM Tuesday book list and give those titles a try. It’s a much less harrowing path than visits from a trio of STEM spirits.

Take it from me. STEM graphic novels and comics are the real deal!

Mike Hays has worked hard from a young age to be a well-rounded individual. A well-rounded, equal opportunity sports enthusiasts, that is. If they keep a score, he’ll either watch it, play it, or coach it. A molecular microbiologist by day, middle-grade author, sports coach, and general good citizen by night, he blogs about sports/training related topics at www.coachhays.com and writer stuff at www.mikehaysbooks.com. Two of his science essays, The Science of Jurassic Park and Zombie Microbiology 101, are included in the Putting the Science in Fiction collection from Writer’s Digest Books. He can be found roaming around the Twitter-sphere under the guise of @coachhays64.

The O.O.L.F Files

The O.O.L.F. Files this month emphasizes the power of visual storytelling in STEM and to celebrate the season, a few links to STEM activities for the holidays. Enjoy!

Superheroes & STEM

- CUNY’s Science & U Series episode, Science & Superheroes

- Heroes and villains: the science of superheroes from Science in School

Comic Einstein!

- General Relativity Interactive Comic from Science Magazine

More Sketchnoting

Holiday STEM