I hope everyone’s year is off to good start! Depending on your climate and interests, hopefully you are getting just the right amount of snow, rain, sun, or beach days. No matter the conditions, winter is a good time for bringing newness—new year, new plans, new lessons, new pages. I’m happily revising a MG historical right now and looking for new ways to enliven the narrative while staying true to plot and character. At the same time, I’m analyzing some new-to-me MG books for my editing job, and I thought I’d share some (hopefully) useful insights on three literary devices you might not immediately associate with MG writing.

You probably know these devices well, but since they don’t necessarily go hand in hand with middle grade curricula, you might not think of them in connection with MG. Generally, middle grades get a fair amount of similes and metaphors, imagery, personification, foreshadowing, and maybe a little situational irony; beyond those, many other literary techniques may not be covered in depth until later junior high/high school, even though examples appear in MG literature all the time.

You probably are already including the following lit devices in your MG writing because they are naturally graspable concepts for most middle grade readers—even though readers may not know the names. Recognizing these literary devices and elevating them as a strategy for revision might bring some fine, original moments to your MG writing—along with a breath of that newness we tend to crave in a project we seek to improve.

Vignettes

A vignette can refer to a short, standalone piece of writing; it can also mean a standalone performance, like one of a series of monologues or scenes in a nonlinear play. But vignettes appear all the time in narrative storytelling as well; look for them as brief sketches or descriptions that don’t contribute to the plot directly but work to more fully convey characterization, setting, or mood.

A vignette can refer to a short, standalone piece of writing; it can also mean a standalone performance, like one of a series of monologues or scenes in a nonlinear play. But vignettes appear all the time in narrative storytelling as well; look for them as brief sketches or descriptions that don’t contribute to the plot directly but work to more fully convey characterization, setting, or mood.

Vignette derives from the French word vigne (vineyard), which probably brings images of connected, trailing, spreading vines. MG vignettes, like literary sketches, are all of those: connected to the story, but leading the reader’s imagination a few steps down a path for a quick glimpse from a new perspective, like in this moment from Lisa Yee’s Maizy Chen’s Last Chance:

The Ben Franklin Five and Dime smells like apples. The handcrafted jewelry and glass jars crammed with colorful candies make me feel like I’ve walked into a treasure chest. A dig bald man in a nubby orange sweater sits at the soda fountain counter. He looks up from his banana split, but when our eyes meet, he turns away, almost shyly. (Chapter 6)

The lens on the story or character (or both) is adjusted and refocused with this descriptive little sketch, but no passage of time or plot event  occurs. Think of a vignette as a time-standing-still moment in which you get to take a good look around. Sometimes the author stops time to build suspense or prolong and heighten emotion, like in this moment early in Sharon M. Draper’s Stella by Starlight:

occurs. Think of a vignette as a time-standing-still moment in which you get to take a good look around. Sometimes the author stops time to build suspense or prolong and heighten emotion, like in this moment early in Sharon M. Draper’s Stella by Starlight:

Besides the traitorous leaves, Stella could hear a pair of bullfrogs ba-rupping to each other, but nothing, not a single human voice from across the pond. She could, however, smell the charring pine, tinged with …what? She sniffed deeper. It was acid, harsh. Kerosene. A trail of gray smoke snaked up to the sky, merging with the clouds. (Chapter 1)

In the time it takes to sniff the air, the author fills the moment with tone, sensory imagery, foreshadowing, and the hint of danger. Vignettes are powerful, swift tools in MG.

Allusions

Allusions are brief references to something that exists outside the scene, typically calling to mind some recognizable name or element from mythology, history, religion, culture, or another story. They are layered with meaning and rely on the reader “getting” the content based on their general familiarity with the topic. They are a quick and punchy shot-in-the-arm of interest for the reader who recognizes them, too, making them perfect for MG—middle graders enjoy coming across an unexpected mention of some bit of knowledge they already know. And you can communicate a complex idea with just a mention of an allusion—sometimes more easily than in explanation.

Allusions are brief references to something that exists outside the scene, typically calling to mind some recognizable name or element from mythology, history, religion, culture, or another story. They are layered with meaning and rely on the reader “getting” the content based on their general familiarity with the topic. They are a quick and punchy shot-in-the-arm of interest for the reader who recognizes them, too, making them perfect for MG—middle graders enjoy coming across an unexpected mention of some bit of knowledge they already know. And you can communicate a complex idea with just a mention of an allusion—sometimes more easily than in explanation.

Think younger with MG allusions; favorite childhood characters, fairy tales, ideas, and stories that have stood the test of time and appear across multiple works or iterations might work well. If you want to get across the idea of an overbearing, oppressive, authoritative character, don’t call them a Big Brother; maybe call them an Umbridge. Ask if your allusions represent only one time period, culture, religion, or group. Consider cultural figures whose renown has crossed cultural divides.

Of course, allusions also offer a great opportunity for an MG writer to sneak-teach readers a new bit of history or culture when the reference might be not-so-recognizable. In Jennifer L. Holm’s Full of Beans (which takes place in Key West in the 1930s), the allusion to the town’s “resident writer” offers the chance to investigate Ernest Hemingway; and in Brenda Woods’s When Winter Robeson Came (set in 1965), protagonist Eden’s piano teacher mentions Margaret Bonds and Julia Perry, Black female composers.

Juxtaposition

The tricky-sounding word belies its simplicity. Juxtaposition is simply the setting up of contrast between two elements (characters, settings, ideas, emotions, really anything) for the sake of highlighting one or both involved. Middle graders are keen on comparison (this is why we introduce and review metaphor and simile so frequently at early middle grades) and with juxtaposition, the meaningfulness is simple and elemental—thinking about what’s dissimilar between two sides speaks to just the right developmental skills of middle grade.

Many MG novels start off with a juxtaposition between the way the protagonist thinks the week (holiday, school day, morning, etc.) will go and the strange, unexpected, or shocking events that really occur. Juxtaposed characters can show a host of contrasts; opposing traits might appear in dramatic foils.

Juxtaposition of setting is key if a protagonist leaves their Ordinary World for another place. Think of how effectively Neil Gaiman sets up the difference between Coraline’s real home and the otherworldly home of her “other mother.”

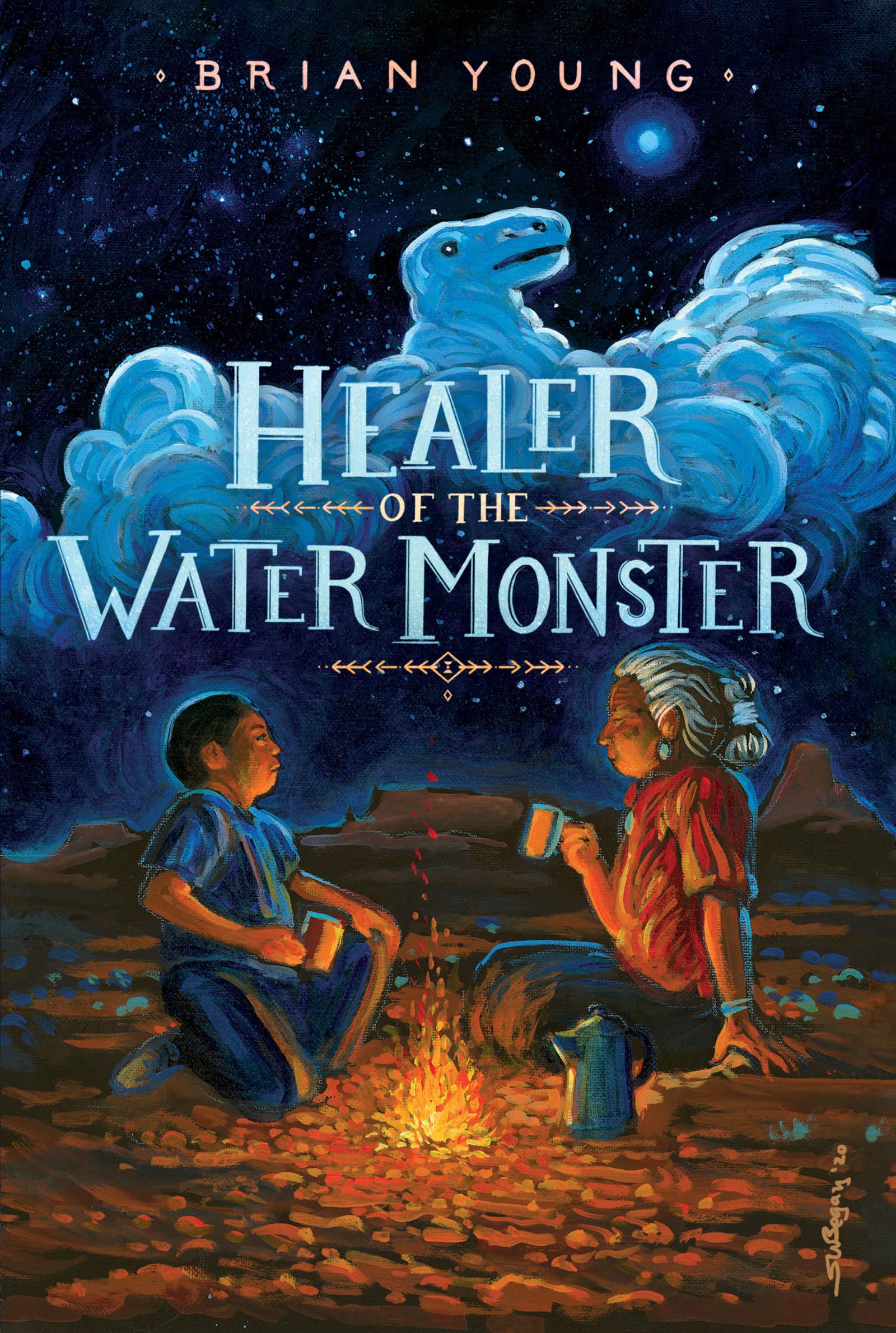

In a more recent example, Brian Young uses juxtaposition to set the stage in his Healer of the Water Monster, starting with the Navajo legend revealed in the Prologue (the gentle Water Monsters who keep the waters “tranquil” and “nourishing” become violent and destructive when Coyote kidnaps one of their infants) and continuing with protagonist Nathan’s big change in summer plans from bonding time with his father on a trip to Las Vegas to—instead—a long stay with his grandmother Nali in her mobile home in the desert. Even the chapter headings show juxtaposition of language with the number first in Navajo, then in English.

In a more recent example, Brian Young uses juxtaposition to set the stage in his Healer of the Water Monster, starting with the Navajo legend revealed in the Prologue (the gentle Water Monsters who keep the waters “tranquil” and “nourishing” become violent and destructive when Coyote kidnaps one of their infants) and continuing with protagonist Nathan’s big change in summer plans from bonding time with his father on a trip to Las Vegas to—instead—a long stay with his grandmother Nali in her mobile home in the desert. Even the chapter headings show juxtaposition of language with the number first in Navajo, then in English.

If you teach middle graders, they might be ready for some brief introduction to these and other lit devices that go beyond the usual study of personification and foreshadowing. They might look for examples of allusions in their class novels, and talk about why the author chose the reference they did. A handy chart or table in their reading journal can be used to compile examples of juxtaposition. And vignettes present an excellent opportunity for creative writing in the classroom; students might try their hand at short character sketches when a “walk-on” character in a class novel inspires description.

Happy writing in this year – I wish you all the best with everything new!

Hena Khan’s

Hena Khan’s  Mayhem features Indian American protagonist Mimi who uses both culinary skill and magic to solve the mysterious goings-on in her household and town. For the Elizabethan classic, consider an introductory adaptation like this

Mayhem features Indian American protagonist Mimi who uses both culinary skill and magic to solve the mysterious goings-on in her household and town. For the Elizabethan classic, consider an introductory adaptation like this  Lou Kuenzler’s

Lou Kuenzler’s  well.

well.

Today, we have a treat for readers who are especially interested in history and historical fiction for kids. Recently, I was delighted to interview Thalia Leaf, who is an associate editor at Calkins Creek. Thalia offered several insights into her publishing imprint and what she looks for in submissions. So let’s get started!

Today, we have a treat for readers who are especially interested in history and historical fiction for kids. Recently, I was delighted to interview Thalia Leaf, who is an associate editor at Calkins Creek. Thalia offered several insights into her publishing imprint and what she looks for in submissions. So let’s get started!

Dorian: What are some of your favorite middle-grade books you’ve worked on and why?

Dorian: What are some of your favorite middle-grade books you’ve worked on and why?