When my children were young, my mom wrote a short seder in rhyme. We wanted them to hear the whole story! This is how it begins:

When my children were young, my mom wrote a short seder in rhyme. We wanted them to hear the whole story! This is how it begins:

In the Torah it says you shall keep the feast

Of unleavened bread—that’s bread without yeast.

And during this feast we’re obliged to tell

The Exodus story til we all know it well.

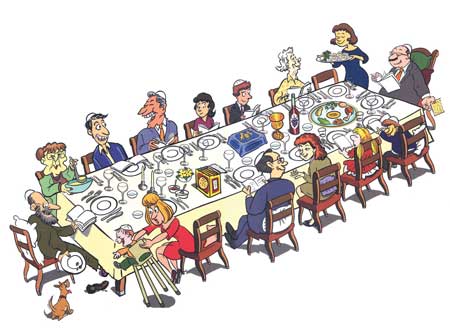

Every year, we tell this story to four named archetypal children.

As presented in the Haggadah, the four children are:

The wise child.

The wicked child.

The simple child.

The child unable to ask.

As a child at my parents’ seder table, this part of the book always made me nervous and upset. Dividing us up into blatant stereotypes seemed like a lose lose proposition. Every year I was sure I was going to be pegged as the wicked one. Or was simple worse? Who were these children? What did it mean, unable to ask?

Here is one explanation, which I found in Jonathan Safran Foer and Nathan Englander’s gorgeous Haggadah, The New American Haggadah. (Note: everyone should own this haggadah. There are great commentaries, including some by Lemony Snicket.)

Here is what they say about the four children:

Perhaps the Haggadah deliberately provides caricatures of four types of children to teach us something about the care we must take when we answer questions. Each person at our seder is coming from a different place. This one is older and more experienced. That one has never been to seder before. That other one was sick and did not expect to make it to seder, but is there. That one never learned to read Hebrew, and that one knows French.

I like that. Thinking this way, the text is talking about different learning styles. (We Jews are so progressive!!!) It’s about communicating with all kinds of kids WITHOUT judgment.

Or maybe….as we discussed last night…this text is also saying something about the nature of story. (The Exodus is a pretty amazing story, after all.)

As a writer and writing teacher, I spend much of my time thinking about novels and writing and reading. I think about what a story needs…and when I think about the best stories, how they’ve grown with me. I think about the times I have heard a story at just the right time! (I also know that there are some stories that seem to change all the time…that I hear or read them differently each time.) That is what happens at the Seder. Even though the story stays the same, it changes and grows with us. Every year, we seem to focus on a different aspect. Sometimes we are wise. Sometimes wicked. Sometimes, we have no idea what to make of the story. Over time, we also get nostalgic. We think. We talk.

A good story inspires new conversations. They bridge generations.

Last night, my son Elliot, who is on the verge of graduation, heard the story as a transition tale. He wondered about Moses’ fears. He is also interested in leadership and we spent a lot of time thinking about Moses’ development from ordinary man to hero. Another student could only focus on the Egyptians who did not believe in slavery, but were subjected to the plagues. Another young person asked if we always need war to free ourselves of atrocities.

What I love about the seder: that story is still relevant!

My mother’s seder ends this way:

What does this all mean? What’s the larger scope?

Why tell of the Exodus again and again?

It’s the preservation and affirmation of hope

This is our covenant with God. Amen.

It’s been written about many times on this blog. Hope is the foundation–and part of most endings–in great middle grade stories. Hope is essential, like conflict and empathy, whether you are wise or wicked or simple or don’t know how to ask.

Happy Passover!!!! Happy Easter!!!

Is there a book that YOUR family rereads? Why? How has it changed for you and your children over the years?

Sarah Aronson used to be a Jewish educator, but now she is a writer who thinks a lot about the Jewish experience in her books.