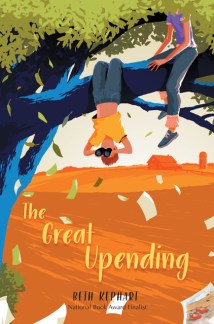

Oh, have I got a treat for all of you today–an interview with National Book Award finalist Beth Kephart. In a time when so many words we hear are sharp and scary and full of darkness, her new book, The Great Upending, is a celebration of truth, bravery, language, and hope. And pies. And pigs and chickens. And … it’s also an adventure. I can’t wait for March 31, when it drops and all of you get a chance to share my excitement.

About The Great Upending

“In The Great Upending (A Caitlyn Dlouhy Book, Atheneum Books for Young Readers, Simon & Schuster, March 31, 2020), Sara Scholl and her brother, Hawk, live with their parents on a family farm among pigs and goats and fabulous chickens, vegetables, and housecats. It’s a happy family, a beautiful place, but there are problems. A drought has set in, money is short, and Sara, who has Marfan syndrome, has been told that her future could depend on her getting medical care that her family cannot afford. Into this world moves an old man, a picture-book artist the children call The Mister, who is renting the family’s renovated silo. The Mister has mysterious troubles all his own, though the children are cautioned against getting involved. Soon the challenges all the characters face merge into a single, life-changing adventure.”

School Library Journal highly recommends The Great Upending! “With exquisite language, the author vividly conveys the beauty of a family farm full of life. Dialogue is spare, which fuels the narrative’s emotional arcs and imbues each character’s purpose with urgency. VERDICT Readers will be drawn into the lush descriptions of setting and moved by the characters’ devotion to their passions whether they be land, art, or one another. Highly recommended purchase for school and public library collections of all sizes.”

Interview with Beth Kephart

HMC: First of all, I want to say how much I LOVE Sara. Oh, this GIRL – she’s full of heart and love and stretch …. More on that word later … you’ve written a character I just want to HUG (gently.)

Okay – so I promised we’d talk about the word “Stretch.” Your main character, Sara, is “a body built out of stretch” and describes her beating heart as “stretch and pull.” Because Sara has Marfan syndrome, “stretch” is loaded with literal meaning as well as figurative. Did you always know this was part of how you’d describe her?

BK: What an interesting question. I’m not sure that I ever know anything for sure. Words occur, images, metaphors, but every language decision I finally make reflects my desire to get both the character right (vivid, true, meaningful) and the sentences alive with sound and sense. So that “stretch” very much captures the condition that Sara lives with, but it is also a word that snaps those particular sentences to attention.

Origin Story

HMC: Sara is based on someone you know—can you tell us more about her and about the origin story for The Great Upending?

BK: Sara is indeed inspired by a young woman I know, a dark-haired beauty named Becca Weust. I had been asked, by a client company named Accolade, to interview Becca by phone about her life and experiences for a planned story. Well, we got on the phone, she started talking, and I was in love. Becca is so smart, so funny, so gracious, and so loving—and she is also living with a very extreme form of Marfan syndrome that has left her spending much of the past six years in bed (and not in college or at work, where she would love to be). Marfan syndrome has forced Becca to undergo seemingly countless surgeries and procedures, much pain, extended isolation, save from family and close friends. Long after my client work was done, Becca and I stayed in touch, sending gifts through the mail, funny emails, pictures.

There are two other origin stories here. One is that the story takes place on a farm where my husband and I led our inaugural memoir workshop; the landscape, the animals, the hill and the big look-out tree are all borrowed from that experience. The other is that the old man in the story, The Mister, is inspired by my own beliefs about publishing in general, but if I say more than that, I’ll ruin the story for readers.

((THE GREAT UPENDING takes place in the middle of a drought. To read another book set during a time of drought, click here.))

Writing For and Not About Becca

HMC: You were committed to writing this book for Becca and not about her. Can you talk about that a little more—and how you were able to support Becca in all of her personhood as opposed to defining her by her condition?

BK: Becca might have been a student on the college campus, where I work. She might have been a daughter; I’d always imagined having one. I didn’t know what to do with the deep affection she stirred, and so I promised her a story.

Not a story about her, but a story for her. Not a biography or an explanation, but a fiction that borrowed the fog of Becca’s tea and the name of her cat and the power of her ambition to live free of the pain riveting her connective tissues. When we write a story for another, we shift the landscape, the community, the weather—translating situation into scene, essence into gravity, pause into momentum. When we write for, we dare to imagine alchemical circumstances—overcome obstacles, emphatic pivots, triumphs of the lasting kind, the might of the right and the good.

For Becca Weust. That’s how my book, The Great Upending, begins. The most important three words in the novel that would not exist but for the young woman who lives half a country away from me, who answers my notes when she can, who did not mind when I promised her a story. Real time tocks. Imagination takes us elsewhere—allowing us to preserve the things we cannot envisage losing and to write the endings that we desperately want for those who, in their many ways, continue waiting.

Writing With Emotional Balance

HMC: Two of the lovely themes TGU investigates are: 1) the need for hope and belief; 2) the concept of tomorrow, which for most children is a given, but for a child who faces devastating health challenges, it’s a dark question mark. No child should ever have to grapple with the worries Sara has to face. You handle her grief and uncertainty with a deft touch, never minimizing it, but also balancing that gravity with delicate and sometimes laugh-out-loud humor. How did you find that balance?

BK: The answer to this beautiful question is that it took me a very long time—years—to strike the right balance. At first, Sara was too grim and her voice too adult. Then she was too young and not sufficiently introspective. I think that when I decided to give Sara her museum of seeds, to really develop that as an image and metaphor, I began to strike a better balance between the time we live right now and the time we hope to have tomorrow.

Blending Writing Styles

HMC: Your writing is stunningly lyrical and begs to be read out loud… “ Catch a bird, catch a beating heart. Catch a bird, catch another day’s eggs. Catch a bird, catch a friend, catch a squawk. Catch a bird, and the fire burns, but it burns less now.” I loved the rhythm and cadence of your sounds and sometimes the unexpectedness of your word choice. For our readers who are also writers and thus always studying craft, I’d love to know a little more about how you blended those two styles without sounding like we were suddenly transported to a different book!

BK: Another great question (they are all great questions). I think I will say this (for there is so much that I could say): My first sentences are always lousy. They are uneven as heck—some too jolly, some overly repetitious, some too insular, as if I’m talking to myself, in my own language. I allow myself to write poorly. I do as much as I can to fix the pages. In this case, my editor, Caitlyn Dlouhy, took out her green pen after many drafts, put loving question marks and comments where they needed to be, and then I started, in so many ways, all over again. By the time I hit the tenth or eleventh draft, I could read the book out loud to myself without experiencing grave disappointment. (Caitlyn kept helping—fewer question marks, always the green pen.) Reading it out loud at that point gave me another whole round of sound fixes.

Truthfully, though, I’m revising my books in my head even after they are published. Can’t stop. Nothing is ever perfect.

Staying Calm During Covid19

HMC: TGU comes out in the midst of Covid19-forced school shutdowns, when so many parents are scrambling to learn how to homeschool their children. You’ve graciously provided us with some lesson plans to go along with this book – thank you so much! I was wondering what you are doing to stay calm and cope right now?

BK: Oh, gosh. Well. Our son has suddenly moved home with us, and we’re all working on this together (in our small house). My father, whom I visited frequently at his retirement village, can no longer be visited. My University of Pennsylvania classes—I had two courses and one research fellowship this semester—have all gone remote. Everyone is looking for answers. My focus has been on finding positive solutions. What can we do in the house that we’ve been meaning to do? How can I stay in touch with my students—and keep them in touch with each other—so that we can keep each other strong? How can I keep my father engaged and active, even at a distance? I tell those with whom I’m speaking that this is a time in history when we are called on to lead—quietly, in our homes (by not panicking), helpfully, in our communities (by keeping our eyes on our neighbors), and consistently with the stories we tell and share. We have hit a wall, all of us have. But we will stand up. We will build ladders. We will find new ways. We have no choice.

(Also, I’m doing lots of baking. Also, I’m taking lots of walks. Also, I, an admitted news junkie, am limiting my intake of news; watching 24 hours a day isn’t going to help.)

About the Title

HMC: Can you tell us about the title “The Great Upending” – without spoilers can you tell us how you came up with that?

BK: This title was a happy dance between my editor, Caitlyn, and myself. We kept circling titles with words like Ending in it, because, well, SPOILERS—I can’t really say. But one day it just became obvious. How about The Great Upending?, I wrote to Caitlyn. And she nodded electronically, as she does.

HMC: What was your favorite part of this book to write?

BK: The end, but I can’t say more than that. The end, because it took me so long to figure out, and then when it was there, when it appeared, like magic, I burst out crying. You’ve been here all along, I said out loud. My characters had known just what they were doing.

Last Thoughts

HMC: Do you have any last thoughts you’d like to share?

BK: It is my great hope that this time of tremendous uncertainty and sadness and upendings can also be a time where broken bonds can heal and communities come together. Books have always been, and can continue to be, a salve. Let’s all become even more committed readers willing to enter into the lives of others during this time.

HMC: Thank you, Beth, and congratulations!

You can listen to Beth Kephart read the first few pages of THE GREAT UPENDING, plus see some wonderful pictures of the farm that inspired the story here.

About Beth Kephart

As the author of more than thirty books in multiple genres, Beth Kephart has been named a National Book Award finalist as well as a winner of the Pew Fellowships in the Arts grant, a National Endowment for the Arts grant, a Leeway grant for Creative Nonfiction, a Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Top Fiction grant, and the Speakeasy Poetry Prize, among other honors. Her books have received multiple starred reviews, been named to Best of Year lists, and been translated into more than fifteen languages. You can find Beth’s website here.

Twitter: @BethKephart

To buy:

Bookshop.org

HOMESCHOOL ACTIVITY

Below are some questions you and your family might consider as you read this book.

- Sometimes, when Sara and Hawk sit outside, they listen to the sounds of their world: “The farm noises There are cows in the cow barn, goats in the goat barn, cats in their cuddle, and the old horse Moe, who snorts like a warthog.” What are the sounds of your world? Make a list, then write a poem so that others can hear what you hear.

- Hawk loves the book Treasure Island so much that he carries parts of it around with him in his Name the book that you love best, then write a letter to the author (even if the author is no longer here) to tell them why.

- Sara has her own private seed Why? What do the seeds mean to Sara? What is your private, or personal hobby? Find a way to document that hobby with just four photographs.

- Sara’s mom can do a lot of things—fix a fence, fight a fire, bake delicious In fact, every member of the Scholl family has special talents. What are they? What do they contribute to the story?

- Kalin is a very special librarian. Draw your version of the World’s Best Library—and the world’s best librarian.

- When you first meet The Mister in this book, what do you believe his story is? How does your impression of him change as the story unfolds?

- Sara and Hawk have been asked, very clearly, not to interfere with The Why? Do you think they were wrong to get involved with him? Should they have told their parents what they were up to?

- The Mister is the creator of famous wordless picture books. Create your own wordless picture Now create a version of this book with words. What is the power of a story without words?

- What do you think the red shoes in The Mister’s picture book symbolize?

- Marfan syndrome is a connective tissue disorder that has affected many famous Research the condition to find out more about its symptoms and the studies now being undertaken to help those who are diagnosed with it.

- The author, Beth Kephart, dedicated this book to a young friend named Becca Weust, who has Marfan. To whom would you dedicate a poem or story of your own? Write and illustrate that poem or story. Write the dedication.

Read this interview with the author, Beth Kephart. What other questions do you have? Email your best one to:

info (at) junctureworkshops (dot) com

Supriya grew up in the Midwest, where she learned Hindi as a child by watching three Hindi movies a week. Winner of the

Supriya grew up in the Midwest, where she learned Hindi as a child by watching three Hindi movies a week. Winner of the